Luca Turin may be right when he says that there is a vibrational mechanism of odorant molecules that can detect odors by tiny biological spectroscopes located in the olfactory epithelium. What happens is that evolutionarily that mechanism has been relegated to the background because it is no longer functionally active. The vibrational mechanism proposed by the biophysicist Luca Turin probably existed thousands of years ago and was subsequently replaced evolutionarily by a stereochemical mechanism, as we know it today and which constitutes the current paradigm of olfaction.

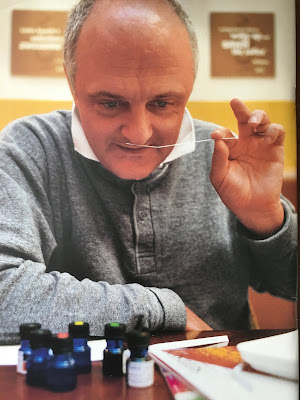

The importance of the theory of Luca Turin lie in that according to it, molecules with the same vibrational wave number in the infrared smell the same. Although the sense of smell does not work that way, it will continue to maintain that ancestral property. From there, a highly efficient odor predictor algorithm can be developed. Luca Turin through companies in which he has collaborated, like Flexitral, has been quite successful with such predictive calculations. A molecule will have a certain odor depending on its chemical structure.

The vibrational mechanism of Luca Turin only refers to the primary olfactory reactionor how the ligand (odorant molecule) interacts with the olfactory receptor (7-transmenbrane protein linked to protein G). From this stage all the successive processes that are part of the olfactory paradigm accepted by the scientific community they are still valid (nature and behavior of the olfactory receptors according Richad Axeland Linda Buck, projection of molecular structures in the olfactory lobe, formation of olfactory sensations in the brain, etc.)

In February 2016, a group of Italian scientists from the University of Trento, led by Marco Paoli published an interesting work that brought new light to the controversy between the stereoscopic theoryand the vibrational one. They checked in bees that isotopic isomers of deuterated odorant molecules activate olfactory glomeruli other than their non-deuterated homonyms. (Two isotopic isomers differ from each other only in that their hydrogen atoms have been replaced by deuterium atoms, an atom identical to hydrogen, but with double mass.)

The researchers also verified that all bee glomeruli are weakly sensitive to the detection of isotopic odorants and that only a part of them are energetically sensitive to that type of detection. The aforementioned activation mechanism is not a substitute for the stereochemist, but could be a complement to it.

When it comes to very similar molecules, such as isotopic isomers, a new way of discovering odors comes into play. The conclusion of this work allows the authors to say that it is possible that the mechanism by which bees capture odorant molecules is of the vibrational type.

Earlier in 2011 Luca Turin and colleagues also published a work on olfaction in the fly Drosophila melanogasterwith similar conclusions to the comment of the bees.

The mechanism of differentiation between deuterated odorant molecules is an obsolete and non-functional mechanism. This would mean that the aforementioned mechanism, generated by evolution, was operational in past times. At the moment it has been in disuse, but it is still there, in the genotype of some living beings.

When did that ability to differentiate isotopes in bees appear? Possibly emerged in the process of evolution of the first insects, more than 300 million years, in the so-called Devonian period. In those times, deuterium was possibly more abundant than now in the Earth's atmosphere, as a result of the Big Bang, and it would not be strange that certain plants synthesized odorant molecules, such as rose, carnation or jasmine, incorporating deuterium to its sap. Evolution allowed the discrimination of its non-deutered homologues. The bees, hundreds of millions of years later, would inherit that special olfactory ability from the first insects.

It is interesting the role played by NADH and the Zn +2, argued by the biophysicist as key elements of his theory. The book of the American journalist Chandler Burr, "The emperor of perfume"is also very illustrative in that sense, which explains in an entertaining way how Luca Turin was building step by step his vibrational theory. The book by Chandler Burr, a former contributor to such important newspapers as the New York Times and the Washington Post, was a bestseller in many countries around the world.

It is assumed that early Cretaceous bees preferred to make their honey with flowers less contaminated with heavy elements, such as the still young isotope of hydrogen. Evolution allowed them to choose what was best for them. Possibly that spring honey, tasty and nutritious, was more digestive for the larvae of the bees than the one coming from plants with deuterium in its sap.

Luca Turin's theory is too elegant and consistent to believe that it isn´t true. Albert Einstein said that a physical law as well as being true must be beautiful.

Bibliography:

- Bridging the Olfactory Code.Francesc Montejo. Perfumer and Flavorist. July 2009. Vol.37, nº 7.

- Differential Odour Coding of Isopomers in the Honeybee Brain. Marco Paoli et al.Scientifics reports. University of Trento. February 2016

- Molecular vibration-sensing component in Drosophila melanogaster olfaction. Luca Turin et al.National Center for Biological Sciences. Bangalore, India January 2011